At the start of walking the Clarendon Way in the summer of 2020, we happened across Clarendon Palace and from knowing absolutely zilch about it, we discovered that, according to the Royal Palace’s website, “Clarendon is quite simply one of the most important royal domestic sites in England”. And it’s been there, almost under our noses for all these years! In fact, Clarendon Palace was around much before the foundation of Salisbury. At its height in the 13th and 14th Centuries it was probably the most spacious royal residence in England and at 4292 acres the largest park in medieval England.

Back in 1065, Edward the Confessor had a manor in Broughton, Hampshire (a pretty village not far from Clarendon). In 1070 William the Conqueror assembled his troops at Clarendon; the site was named in documents for the first time in the 12th Century. It’s believed that Henry I, during his reign (1100-1135) laid out a park and upgraded a residence at Clarendon. In 1130 Henry I and his queen, Adela of Louvain visited. During the reign of Stephen (1135-1154) the Augustinian Ivychurch Priory was founded on the southern border of Clarendon Park. From 1154 there is documentation of mews (huts of wood and wattle) for the king’s birds of prey at Clarendon. In 1164 the Constitutions of Clarendon were sealed by Henry II and Archbishop Thomas Becket, limiting the clergy’s legal rights. This event led to Becket’s exile and his subsequent murder in Canterbury Cathedral just 6 years later. Clarendon was also described at this time as “that noble and preeminent mansion, the king’s own, from its name and prominent position called Clarendon”. Garden and building works were carried out; Henry II spent more on Clarendon than on any other of his 20 rural retreats. Around 1200 gryfalcons (the largest falcon) were brought to Clarendon for the king – they were the largest hunting bird and usually only used by royalty. Gryfalcons came from Norway and were prized for use against cranes, herons and ducks in particular. In 1207, Queen Isabella, pregnant with Henry III was escorted to Clarendon.

In 1220 the original location of the Cathedral at Old Sarum was established. In 1227 Henry III ordered Clarendon Park to be enclosed and in 1228 Clarendon Forest was established. A new chapel was begun at Clarendon in 1234 and the Great Gate was built in 1241. In 1244 new stables were built next to the old hall as was a herb garden. In 1268 a prison was ordered to be built at the palace. Throughout Henry III’s reign, large consignments of food and wine were sent to Clarendon until his death when the palace and park were found to be in poor repair. Under Edward I’s reign a survey of the palace and park confirms this. During Edward II’s reign, a court hears of ‘the forcible entry of the king’s manor of Clarendon by Robert de Micheldever (deputy warden) and others, carrying away timber, stones, iron, lead and other goods’. In 1314 gangs of men including those in the household of the king’s enemy, the Earl of Lancaster, enter Clarendon Forest with bows and arrows, snares and dogs. Edward II visited and hunted in the park; on one visit he took ‘88 great fallow bucks and 14 (young bucks)’ in the park. Under Edward III major works were done in the palace and the park, including new coppices to be made in the park; they are probably the coppices that survive today. The works continue during the reign of Richard II (1377-1399) including the introduction of a ‘Dancing Room’.

During Henry VI’s reign, he suffered from either catatonic schizophrenia or an extreme depressive episode whilst at Clarendon Palace in 1453; he stays for one of the longest recorded royal visits at Clarendon. Richard III probably carried out the last round of building works at Clarendon. In 1535 it’s believed that Henry VIII visited and in 1574 a feast was held for Elizabeth I. In the late 1640s under Charles I, Clarendon Park estate is sold to pay off war expenses, oaks are plundered from the park and deer are hunted – by 1661 no deer are left and the park passes out of royal hands in 1664.

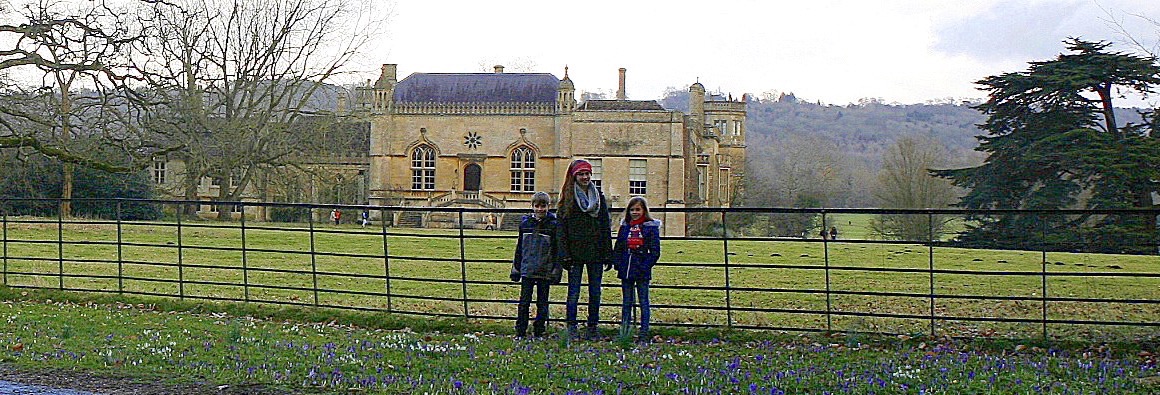

Clarendon’s deterioration continued until 1801 when the Wiltshire antiquarian, John Britton reflects “The habitation of kings is levelled with the dust and all the proud revelry of a court has given way to the hooting of the owl and the croaking of the raven”. In 1824 Frederic Hervey-Bathurst (of the wealthy Bathurst slave-trading family) inherited Clarendon Park. He made changes to the building making it twice as large which meant twice as expensive to run and together with the consequences of the agricultural depression of the 1870s, debts ran up leading to the estate being sold. Under the ownership of the Christie-Miller family in 1919, excavations were begun under the world renowned Finish art historian, Tancred Borenius, who believed the excavations “offered a field of study which is prime importance for the medieval archaeology not only of England but of the whole of Europe”. Many finds from these excavations of the 1930s can now be found in the British Museum and the Salisbury Museum. Nikolaus Pevsner, the German British art historian and architectural historian visited in the 1930s and suggested that the palace should be rebuilt. He wrote of Clarendon “… today Clarendon is a tragedy. … One crag of wall stands up. All teh rest is back to its sleeping beauty. Surely, out of respect for English history if for no other reason, these remains ought to be as clearly visible as those of Old Sarum.” In 2006 the estate was bought by a banker, Marc Jonas and his wife.

So, what is left of the original great Clarendon Palace remains a quiet open space with a collection of dips and hollows, crumbling steps, roofless chambers and the occasional flint wall, requiring imagination to take you back to the days when it was a palace with a Great Hall, a falconry mews and more. Today the resident llamas – and dedicated Friends of Clarendon Palace – keep a check on nature and continue to make discoveries at the site. I would recommend a visit – take a picnic, it’s a beautiful walk from Salisbury to the site and the views are glorious, particularly on a clear day. Let your imagination take you back to a time of great celebration when a feast was prepared for the visit of the powerful Elizabeth I or to a time of disharmony between monarch and church (Henry II and Thomas Beckett); it is incredibly evocative. And the llamas are a delight!